National article: Best apps that make life easier in your community

December 22, 2012

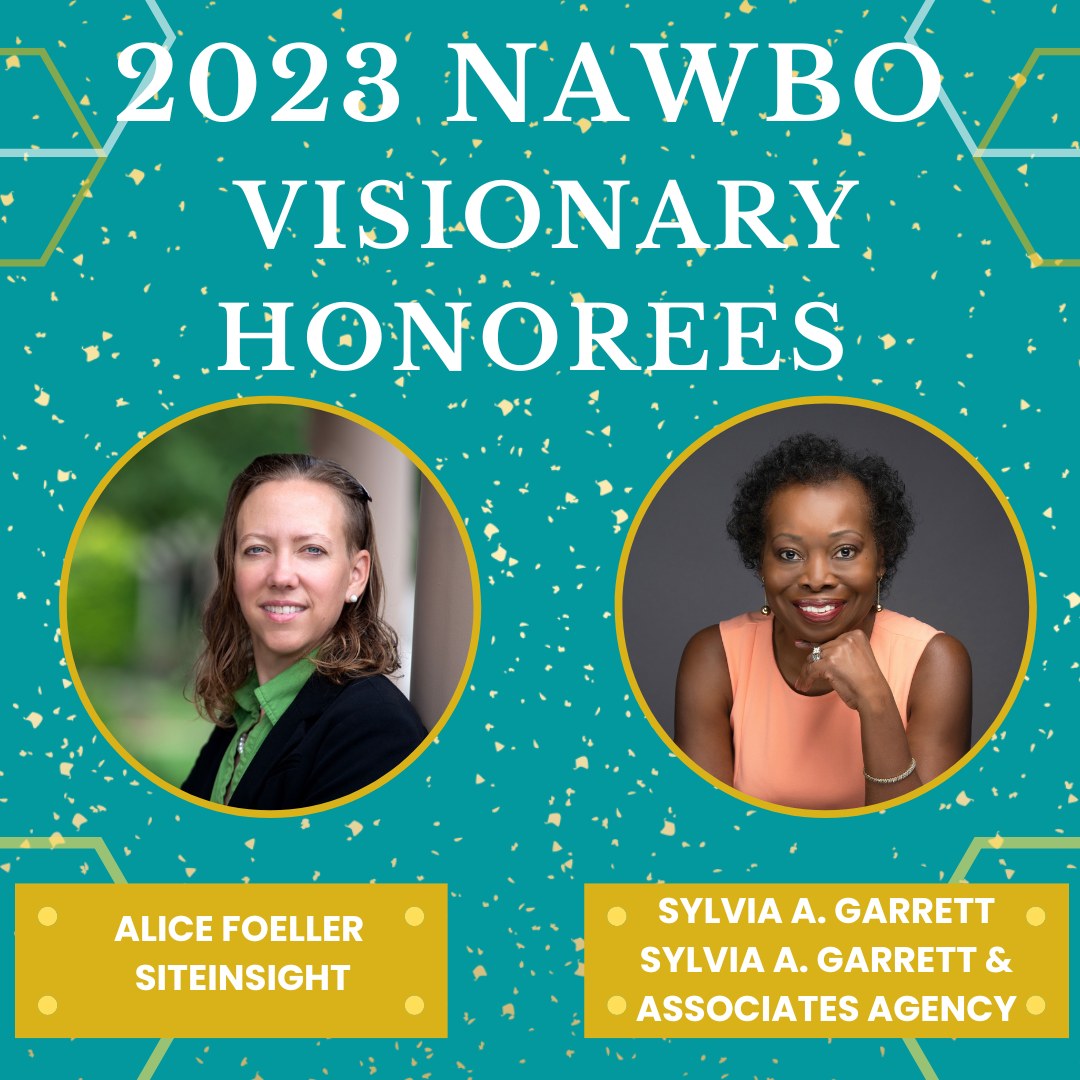

Alice Proud to be Selected NAWBO Visionary Award Winner

April 4, 2023THE WHY – For Those Who Were Surprised

By Alice Foeller

We’ll start with Daniel’s voice, but it’s the exacting voice of a Daniel in severe pain, writing his suicide note.

“Why? This isn’t anyone’s fault, no one is to blame, and no one could have done anything to help. I’m desperately tired of living in a world that doesn’t even remotely share my values or focus, and I also believe there is absolutely no point or higher purpose in life or existence. Additionally, my future feels increasingly bleak with diminishing hope of improvement (depression, anxiety, reclusion, aging, boredom, frustration, futility). Please disclose the cause of my death and these exact reasons freely to whomever wants to know, I don’t want there to be any confusion or misunderstanding in anyone’s mind as to why I did this.

-Daniel”

Listening to him talk about his childhood, I just wanted to scoop up that little boy and hold him, away from his mother, a beautiful woman addicted to prescription drugs, who wrote in her journal, “I never wanted Danny.” I wanted to hold him protectively against the force of his single-minded father, who was holding the household together and seemed to have only the capacity to give approval in exchange for performance.

But maybe no amount of scooping or holding would have helped, even back then. Who knows.

He overcame a lot of fears and transformed a lot of unhealthy thoughts.

By the time he died at almost 52, he could fly on commercial planes without anxiety meds. He could work (and even sleep) in tall buildings. He believed mothers could love their sons. He believed I could love him. (And I did.)

But just like when you are planning to break up with someone, you don’t let in any good thoughts about them; and he was planning to break up with life. Some beautiful, kind, loving things happened in those last weeks, and he couldn’t bring himself to look, lest it hurt too much to turn his back on it.

He had always been planning to break up with life. His first suicide attempt was just after college, when he moved away from the nature that sustained him, and into a loud, crowded New York City, sharing an apartment with strangers and working at a frustrating job. The second was after a breakup with a beloved girlfriend. Those were the serious ones. There were also the casual discussions of what he wanted at his memorial gathering. The logistical considerations he would share, when he wasn’t in crisis, of how to do it in a way that wouldn’t leave a mess. The discussions about how I’m so strong, and I would manage to go on with my life. And maybe you are reading this and thinking, “Hey, if he was having suicidal ideations, why didn’t you get him help?”

The easy answer is that he WAS getting help. He was seeing a therapist weekly. He was always reading and listening to podcasts, and sometimes enrolled in personal development courses. He refused anxiety and depression medications. (His sexuality was central to his self-image and his ability to receive love and pleasure, and the side effects of those medications would have impacted that in a way he wasn’t willing to experiment with.) But he was seeing an endocrinologist and taking supplemental hormones and vitamins to optimize his physical and mental health. He had a CPAP machine on order to help him get better sleep, but it hadn’t arrived yet. There was always some magic bullet he was seeking. Maybe just a little more Vitamin D. Maybe a different pillow. Maybe HGH. Maybe microdosing mushrooms. Maybe the next TED Talk.

The harder answer is that Daniel always told me not to talk people out of suicide. “It’s a valid choice,” he would say. “If someone wants to check out, they should get to check out.” It’s just a shame that they must do it in secret because there’s no legal way to do it in community with others, or holding the hand of a lover. But he also had to do it alone because, like the analogy about breaking up a relationship, he had already chosen this path. If a little love or hope had crept in, it would have only taken more time and struggle to push it out the door so he could turn back to the comfortable, empty, quiet despair.

In the final week, some of the things he said to me were:

“I front-loaded a lot of work when I started [my job at] Keyfactor. I worked on my virtual lab every weekend for weeks when I started, to learn the software. And I left there after such a short time, it didn’t pay off. And then I did the same thing at Tanium. I worked so hard for months, and it was just going to start paying off, and then I got laid off. I just don’t think I can do this one more time.”

“I just don’t know if I want to work through this one.”

“No matter how much I cry, no matter how many people I hug, no matter how many calls I make I can’t get the pain and the fear out. I just want it to stop.”

“Admit it, wouldn’t some part of you be better off without me?”

I told him that the layoff was a blessing, and the “golden handcuffs” were off. He wasn’t going to find a job like that again anytime soon in this economy with all of the IT layoffs, numbering in the hundreds of thousands. So there. That’s gone. Just leave the corporate culture and go do something that makes you happy. I sent him a job listing for a stable hand at the Otterbein University equestrian program. He wouldn’t even click on it. “I just don’t even see how that would work,” he said. I told him he only had to make it for 18 months, until my youngest was off to college and we combined households. I told him I had lived on the cheap for many years and would be quite happy without fancy restaurants. I told him he just had to believe me – believe, dammit – that we were going to grow old together, and this was just a bump in the road.

When we met, Daniel was 43. He shared a playlist of music with me, and all of it was dark, sober … excruciatingly sad. I asked him if he thought he always would be bent toward the sadness. In a moment of optimism, or perhaps just trying to win my affection, he said no. He said he was confident that if he felt safe and loved and had a good outlet for his talents, he could be happy. But he also said, in a different conversation around the same time, that his exit plan was to die (on purpose) in a fiery motorcycle crash at age 45. “I’m not having a great time at this party,” he said. So I figure we—you, me, all Daniel’s family and friends—got him seven extra years. Or we got ourselves seven extra years of him.

He did see the way we love our children fiercely. He did see the profound beauty in flowers and bugs and dogs and birds. He did see the kindness. We did share his values and his focus. But at the end, when he just didn’t have any more left in him, he had to turn away from that so he could find his peace and end the suffering, finally. He had to focus only on the war, the pollution, the injustice, the insecure nature of love, the unstoppable aging of the body, the stumbling economy and the unknown of what might lie ahead. That was the only way he could take an action that would stop the pain.

He told me for years that he woke up every morning feeling terror or dread. I would rib him about his refusal to try exercising in the morning instead of the evening. But in reality, waking up to face the day took an extraordinary act of courage for Daniel, and starting it early seemed unthinkable. But wake up he did, pushing through the dread and rarely taking a day off.

He was brave to wake up every day for almost 52 years. And he was brave to take those pills on the night of January 21st, and tuck himself in with the blanket on the couch (just like he always did), and to take off his glasses, his watch and his earring, (just like he always did), and pull his fleece hat down over his eyes, and go to sleep knowing he wasn’t ever going to wake up again.

Don’t tell yourself you could have stopped him.

Don’t tell me he was selfish.

Don’t say it couldn’t have been that bad.

This wasn’t easy for Daniel. It wasn’t easy to live. It wasn’t easy to die. It must have been really bad. I knew it was really bad. I walked with him for hours. I held him. I reassured him. I coached him. I looked him straight in the eyes, even when he had tears in his. And for me, with my nice well-adjusted brain and my normal happy upbringing and my natural inborn resilience … yes, I certainly could have coped with that adversity. I could have gotten up again. I could have worked through it. But Daniel couldn’t. And we must forgive him that.

And for heaven’s sake, LIVE.

Live your life.

Love as much as you can. Right now.